Beyond 'Great Job': The Evidence-Based Guide to Developmental Feedback

Evidence backed advice for leaders, managers, experts, coaches and mentors on how to give developmental feedback.

In the interest of providing multiple means of engaging with this blog, below is the podcast style conversation, using our AI friends Johnny and Joanne. I have also done a voice over of the original blog, or below is the usual written format.

Remember Gordon Ramsay's Kitchen Nightmares? The shouty chef would storm into failing restaurants, tear apart everything from the decor to the cooking. While entertaining for television, this style is less effective for sustained performance through learning. This archetype of feedback is seen not just on TV, but the side of sports pitches from parents and coaches, and it perfectly illustrates what we get wrong about feedback in organisations. Like those restaurant owners, we often confuse short term improvements in performance with learning and immediate results with sustainable change.

In a previous blog, we explored why experts often make the worst teachers - their expertise can actually hinder their ability to break down and communicate what makes them successful. Ramsay perfectly exemplifies this expert's trap. His exceptional cooking skills and years of experience have become so automated that when he sees a struggling chef, he can't understand why they don't "just get it." Sound familiar in your organisation? The senior leader who can't understand why their team "doesn't see the obvious solution," or the technical expert frustrated by others' "basic mistakes." This frustration often means they resort to the wrong sort of feedback.

In my work with organisations, there's rarely a shortage of opportunity for feedback. The problem is that most of it is as effective as Ramsay screaming about raw chicken – it might get immediate compliance, but does it create lasting learning? This brings us to an uncomfortable truth that challenges much of what we do in HR and leadership development: the most common feedback practices are optimised for short-term performance at the expense of long-term learning. When we talk about knowledge transfers, mentoring or the 70/20/10 learning model, the way you provide feedback is critical for learning in development. The below quote perfectly exemplifies how we should be guiding learners-

Learning is not about the repetition of a solution, but the repetition of finding a solution. (Gray, 2022)

Before we dive into the evidence, let's address a fundamental question that most feedback models ignore: What is the goal of your feedback? If you're trying to prevent a critical error in a high-stakes situation, you need a different approach than if you're developing future capabilities. It's the difference between teaching someone to pass their driving test versus becoming a racing driver.

Let's break down what the research tells us about effective feedback for learning, and more importantly, what it means for your practice.

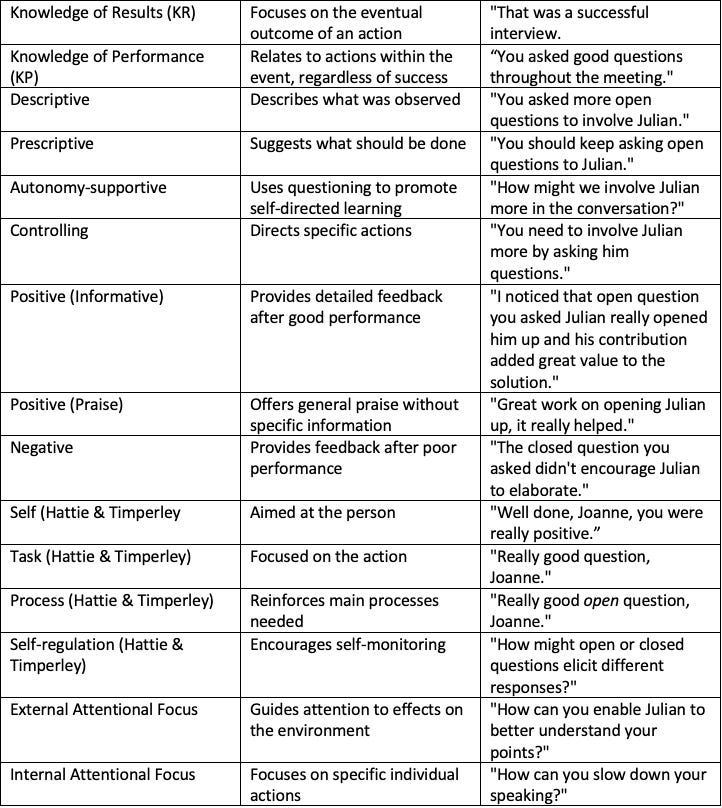

The Feedback Toolbox: More Than Just Results

Imagine you're teaching someone to deliver presentations. Telling them "That was a great presentation!" (Knowledge of Results) is like telling someone the answer without showing them how to solve the equation. It might feel good, but it doesn't help them improve. Instead, noting "Your use of pauses after key points really helped the audience absorb the message" (Knowledge of Performance) gives them something concrete to replicate and build upon.

This brings us to our first practical shift: move beyond the what to the how. The knowledge of performance approach allows specific repeatable advice. In addition it does not need to of been a “great presentation” to deliver it.

The Secret Sauce: Autonomy vs Control

Here's where most of us trip up. When things aren't going well, our instinct is to grab the wheel. "You need to make more eye contact" or "Always start with an agenda" might seem helpful, but they're controlling feedback that can create dependency and reduce learning. Instead, try autonomy-supportive approaches:

Instead of: "You should have involved Sarah more in the meeting."

Try: "What opportunities did you notice for involving the quieter team members?"

But here's the nuance many miss – autonomy-supportive doesn't mean throwing people in the deep end. You can scaffold the autonomy based on experience:

Novice: "What questions might help us understand Sarah's perspective?"

Experienced: "How might we create more inclusive discussions?"

The Performance Trap

Let's tackle a common misconception that's costing us learning opportunities: the difference between praise and positive feedback. They might seem like cousins, but they're actually distant relatives with very different effects on learning.

Here's where the research gets interesting: learning is better facilitated if feedback is provided after good trials rather than poor ones. Yet in most organisations, we save our detailed feedback for when things go wrong. We're literally choosing the worst possible moment for learning. This is not to say we can’t give critical feedback, but unless it is safety critical, focus more on reinforcing what went well and why over focussing on what went wrong and what they should do instead. But this is not the same as just praise.

Think of praise as a chocolate bar - it gives an immediate sugar rush but doesn't provide much nutritional value. "Great presentation!", "You're really good with clients!", "Excellent work on that project!" All feel good in the moment, but leave the receiver nutritionally starved when it comes to learning.

Positive feedback, on the other hand, is more like a well-balanced meal. It nourishes future performance by highlighting specific actions and their impacts. But here's the crucial distinction: positive feedback isn't just about being positive - it's about the level of information you provide that guides future performance.

For example:

Praise: "Great work on opening Julian up in that meeting, it really helped!"

Positive Feedback: "I noticed that open question you asked Julian really opened him up, and his contribution about supply chain constraints added great value to our solution."

Let's look at more real-world examples:

Meeting Facilitation:

Praise: "You ran that meeting really well!"

Positive Feedback: "I noticed how you summarised key points after each discussion. This helped maintain clarity and kept us focused on the objectives, especially when the debate got heated about the budget cuts."

Team Leadership:

Praise: "You're really good at developing your team!"

Positive Feedback: "I've observed how you create learning opportunities in team meetings by asking 'what if' questions instead of providing solutions. This has led to team members like Sarah and John starting to problem-solve independently."

The Formula for Effective Positive Feedback:

Specific Action: What exactly did they do?

Context: In what situation?

Impact: What effect did it have?

Future Value: Why does this matter going forward?

The real power of positive feedback lies in its ability to make effective behaviours repeatable. When someone receives praise like "great job!", they're often left wondering what exactly was great and how to replicate it. In contrast, positive feedback creates a clear path to reproduction and refinement.

By focusing our detailed feedback on successful moments rather than failures, we're not just making people feel good - we're creating optimal conditions for learning. Think about it: when are people most receptive to understanding the nuances of what worked and why? When they're basking in success or when they're recovering from failure? Again, I am not saying feedback should only be positive, but get the balance right. Especially in novices.

Levels of Impact: Beyond the Surface

The Hattie & Timperley (Corbett et al., 2024) model gives us four levels to target feedback:

Self: "You're really good at this" (Least effective)

Task: "That question worked well"

Process: "Your open-ended questions encouraged deeper discussion"

Self-regulation: "How might different questioning techniques affect team engagement?"

High-performing coaches spend most of their time at levels 3 and 4. Yet most organisational feedback hovers between 1 and 2. We're leaving learning potential on the table.

The External Edge

Want to supercharge your feedback's effectiveness? Focus externally. Instead of "Speak more slowly" (internal), try "How can you help the team absorb your key messages?" (external). This subtle shift moves attention from mechanics to impact, often leading to more creative and effective solutions.

Practical Application: A New Framework

So what does this mean for your next feedback conversation? Here's your evidence-based checklist:

Clarify your goal: Learning or immediate performance?

Focus on good trials: What's working and why?

Use autonomy-supportive questions matched to experience level

Target process and self-regulation levels

Frame feedback externally around impact

Provide knowledge of performance over results

The Uncomfortable Truth

Here's the challenging part: implementing this approach might initially feel less effective. You might not see immediate performance spikes, in fact short term performance may get worse. Your feedback conversations might feel less directive and more messy. But remember Gordon Ramsay – dramatic immediate changes rarely lead to sustained improvement.

The question isn't whether your feedback gets immediate results, but whether it creates the conditions for continuous learning and adaptation. In a world where the half-life of skills is shrinking rapidly, which would you rather build: performers or learners?

What feedback conversation will you try this on this week? How might you get some feedback on your feedback?

Summary of terms table

Corbett, R., Partington, M., Ryan, L., & Cope, E. (2024). “All Feedback is Beneficial”: A Deconstruction of Feedback . In A. Whitehead & J. Coe (Eds.), Myths of Sport Performance (pp. 61–77).

Gray, R. (2022). Learning to Optimize Movement, Harnessing the Power of the Athlete-Environment Relationship. Perception Action Consulting & education LLC.