Why Did the Chicken Cross the Road? A Systems Thinking Approach to HR"

A starters guide to using systems thinking to understand organisational behaviour

Please hit the ❤️ “Like” button at the bottom of this article if you enjoy it. It helps others find this article.

Why did the chicken cross the road? It's a classic joke, but let's pause before we rush to the punchline. This seemingly simple question can actually teach us a lot about systems thinking – a crucial skill for HR practitioners and leaders navigating the complex world of modern organisations.

Throughout my blogs, I've often touched on the idea of understanding and acting within complex systems. Whether it's how we think and behave as individuals, how individuals interact with their environments, or how organisations function as a whole, systems thinking provides a powerful lens for analysis.

As a western millennial, I grew up with ways of viewing the behaviour of things based on linear relationships: more equals better, or "who started it" This carried over into business practices, like root cause analysis using the '5 Whys' technique. But let's expand beyond this linear thinking and introduce a systems thinking approach. We will start with a thinking exercise using a traditional linear way of thinking, with our chicken crossing the road example:

Why did the chicken get run over by a car when crossing the road?

Why might that of happened?…..

Why might that of happened?…..

Why might that of happened?…..

Why might that have happened?….

And finally, why might that of happened?

I apologise for the chicken morbidity of this example. But now, pause and think – where did your analysis lead you? Did you focus on the chicken? The placement of the road? The driver? Each starting point takes you in a different direction, potentially missing crucial interconnections.

The '5 Whys' isn't inherently bad, but like all models, it has limitations. It invites us to look at each element independently, potentially overlooking the interplay between factors.

Systems thinking, on the other hand, is about interdependence and two-way causality at a minimum. Instead of asking why the chicken crossed the road, we might ask: "What is the relationship between cars and chickens being run over?" Or "How does the positioning of roads relate to chicken behaviour?"

This shift in perspective allows us to draw a simple causal loop. On one side, more (+) chickens lead to more eggs, which leads to more (+) chickens, creating a positive feedback loop. On the other side, more chickens result in more (+) road crossings, leading to more collisions with cars, resulting in fewer (-) chickens – a balancing (negative) loop.

This systems approach helps us understand how the immediate system of chickens, cars, roads, and collisions interact. But when should we use linear approaches versus systems thinking?

(An Introductory Systems Thinking Toolkit for Civil Servants - GOV.UK, 2023)

In organisational behaviour, statements in the second column are becoming more common, yet the tools we often use are from the first column. This mismatch can lead to ineffective solutions and unintended consequences.

Using a systems approach allows us to understand the behaviour of a system through three key elements: stocks, flows, and delays.Understanding these components is key to grasping how systems behave over time.

Stocks: The Building Blocks of Systems

Stocks are accumulations within a system - think of them as reservoirs or inventories. In our chicken scenario, stocks include the number of chickens, eggs, and even cars on the road. For HR practitioners, stocks might be the number of employees, open positions, or trained managers.

Why are stocks important? They represent the current state of the system and often the metrics we care about most. Just as a chicken farmer cares about their chicken stock, an HR practitioner might focus on employee headcount or the stock of critical skills within the organisation. For a finance practitioner it might be cash.

Stocks also provide buffers against sudden changes. If a large number of chickens unexpectedly cross the road on one day, leading to unfortunate collisions, the remaining stock ensures the population can recover. Similarly, if your organisation faces sudden attrition, having a stock of well-trained employees or a robust talent pipeline can help maintain stability.

Flows: The Dynamics of Change

Flows represent the rates of change in stocks over time. They're like taps filling or draining our reservoirs. In the chicken world, successful reproduction increases the inflow to the chicken stock, while road accidents represent an outflow.

For HR, inflows might include new hires or employees gaining new skills, while outflows could be resignations or skill obsolescence. Understanding these flows is crucial for managing your human capital effectively.

The balance between inflows and outflows determines whether a stock grows, shrinks, or remains stable. If your rate of new hires (inflow) matches your attrition rate (outflow), your employee headcount (stock) will remain constant. But what happens when these flows aren't in sync?

Delays: The Hidden Influencers

Delays represent time lags between actions and their effects in the system. They're often overlooked but can have profound impacts on system behavior.

In our chicken scenario, there's a significant delay between an egg being laid and a new chicken reaching maturity to lay its own eggs. This delay can lead to interesting population dynamics. If the delay is long, we might see bigger variances in chicken populations over time.

Consider a scenario where many chickens are involved in road accidents one day. The immediate effect is a reduction in the chicken stock. This will quickly (short delay) be reflected in reduced egg production, but much longer (longer delay) for the adult chicken population to recover due to maturation delays. Once they have reached maturation they are then able to escape towards the road.

These different delay lengths in the same system can lead to complex and sometimes counterintuitive behaviours. Especially, if we start increasing flows to make up for delays. Let’s say the Farmer just buys in more fertilised eggs from outside their own chickens system in an attempt to get the chicken population back up quickly. We will end up with a bigger peak mature chicken population. Which results in more chicken escapes and more accidents. But no greater chickens over the long term. This is the systems default position, within certain parameters.

The flu virus provides another illustrative example of delays. The delay between infection and symptom onset allows the virus to spread widely before the infected person isolates themselves. If this delay were shorter (like with Ebola), the spread might be more limited. If it were longer, the spread could be even more extensive.

This systems view puts the chicken at the centre of the loop, which might be crucial for a chicken farmer. But what about a car repairer? Their focus might be on cars without chicken-shaped dents. What stocks, flows, and delays would affect their "unblemished car" stock?

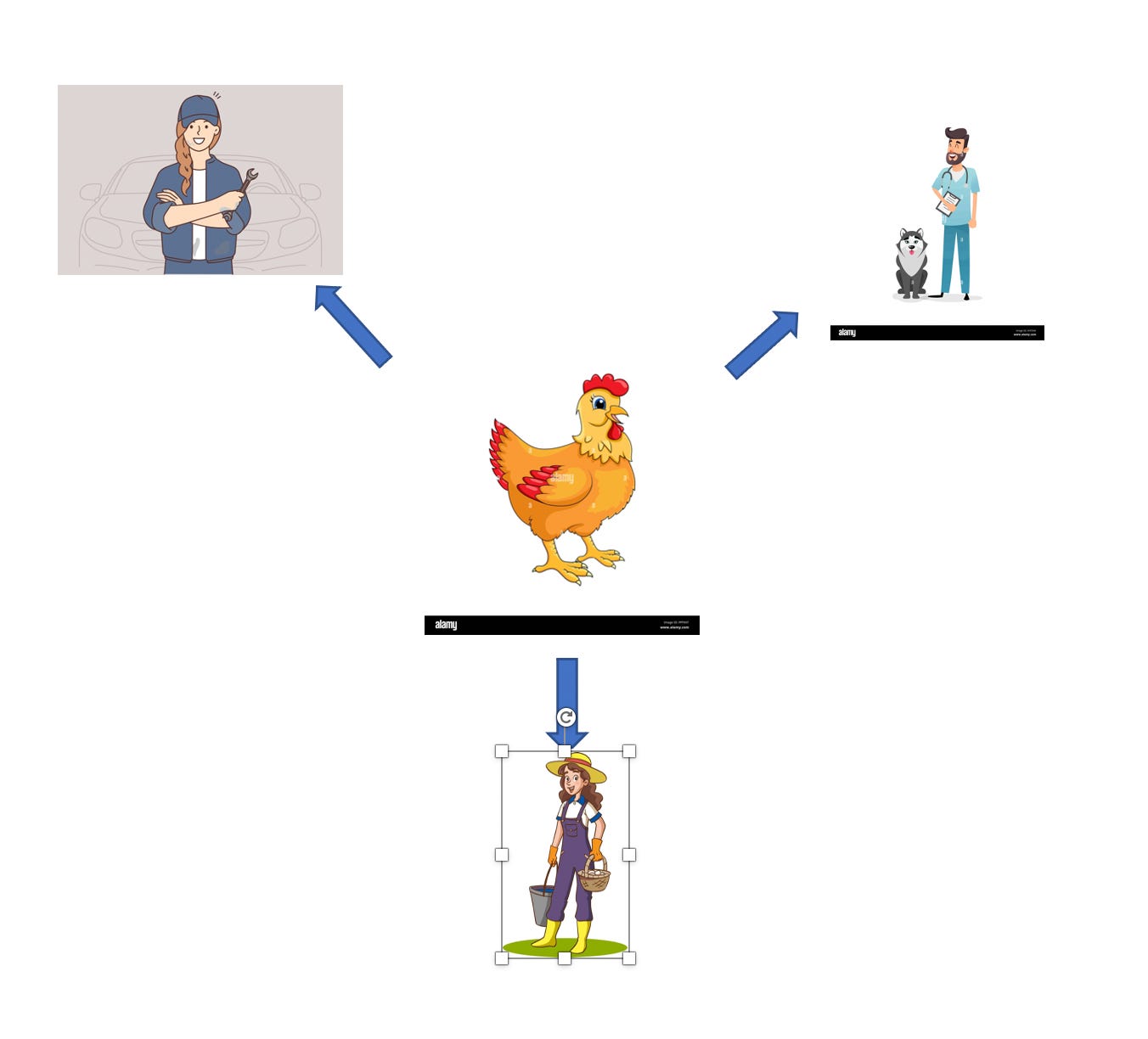

Before mapping a system, it's crucial to understand your perspective. The PIG tool can help here. Just as a pig might be seen as income by a farmer, food by a person, or a patient by a vet, any system can be viewed differently depending on your standpoint.

To use the PIG tool:

1. Decide on the problem or system you're analysing

2. Ask "Who is it seen by?" Farmer

3. Ask "What is it seen as?" Chicken egg producers and income

There's no right or wrong boundary, but this process helps identify the major stocks, flows, and delays relevant to your perspective.

Of course, we can replace chickens with staff, cars with poor managers, and eggs with recruitment activity. More staff requires more managers, which can lead to more poor managers, leading to higher attrition, necessitating more recruitment, and the cycle continues with different flows, delays, and stocks.

As HR practitioners and leaders, understanding these system dynamics can provide invaluable insights. It can help us anticipate unintended consequences of our interventions, identify leverage points for change, and develop more holistic, effective strategies.

In my next blog, we'll delve deeper into identifying leverage points within these systems. For now, start thinking about the causal flows you see in your organisation. What stocks are you trying to manage? What flows are you controlling? And what delays might be influencing your outcomes? The answers could open up a new way of delivering behavioural change.

References:

An introductory systems thinking toolkit for civil servants - GOV.UK. (2023, January 12). GovermentOfficeforScience. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/systems-thinking-for-civil-servants/toolkit#policy-design-stage-confirm-the-goal-and-understand-the-system